How to Take Part in Nationwide Project The Great Big Dialect Hunt - Record Your Own Voice

Living North speaks to Dr. Rosemary Hall to find out more...

The Great Big Dialect Hunt is a National Lottery Heritage-funded initiative searching far and wide to record the dialects of the UK’s towns, villages, and cities – taking a snapshot of their cultures through the beauty of words.

The UK is unique in that by driving up the road for just 10, 20, or 30 minutes you can come across countless dialects, all with their own inherited words, phrases, and language.

This is particularly clear in the North East, with the examples of Geordie, Mackem, and Smoggie accents coming to mind.

Dr. Rosemary Hall is an impassioned sociolinguist and together with her research colleagues she’s recruiting an army of public volunteers through The Great Big Dialect Hunt, giving you the opportunity to record your own dialect, submit answers to lexical surveys, and help document the history of your area – as Rosie explains.

‘We are going up and down the country hunting dialects and recording the different words people use for different things,’ says Rosie.

‘We want to know what’s changed and what hasn’t based on a survey that was conducted in the 1950s and 60s by the University of Leeds.

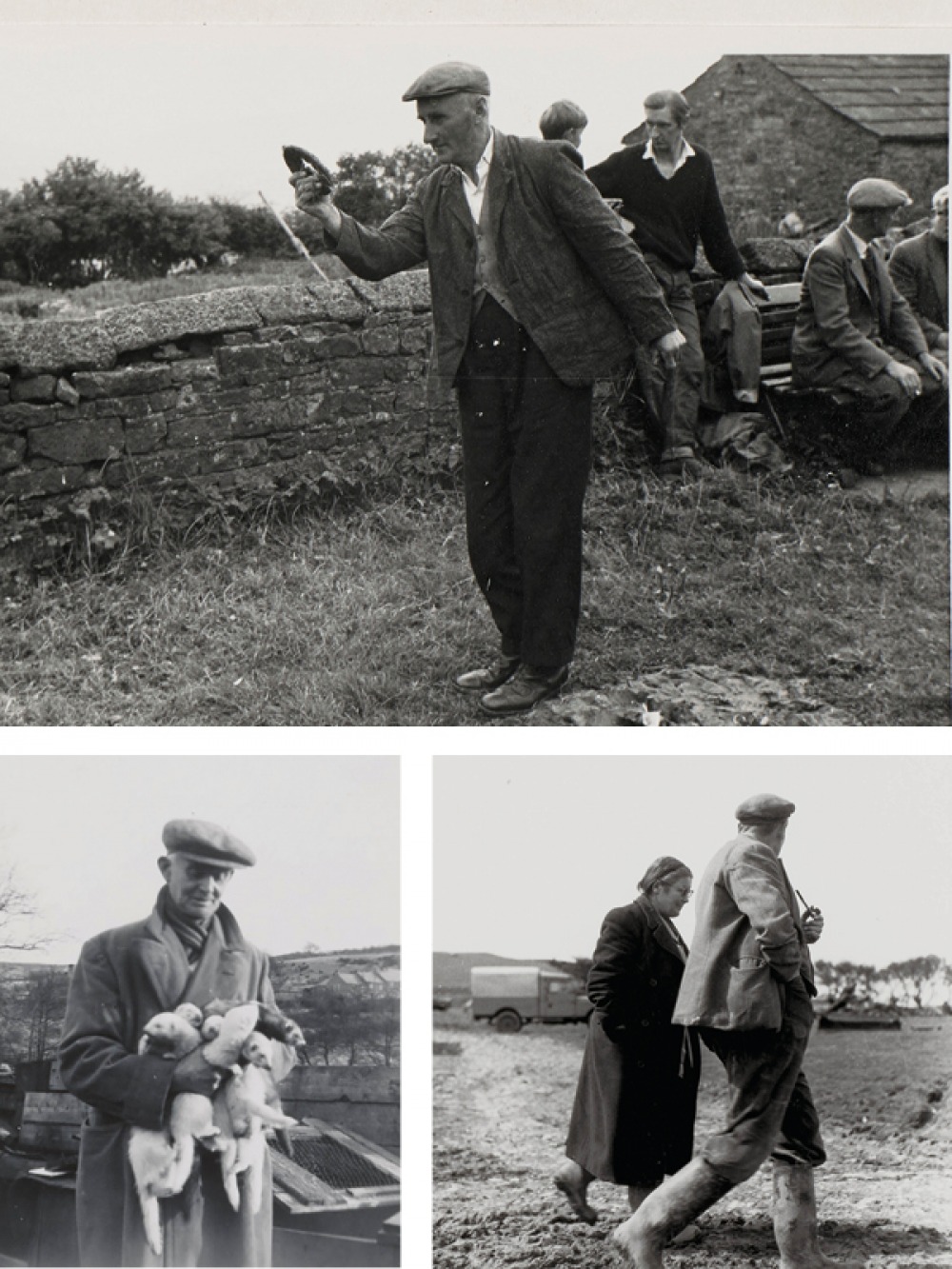

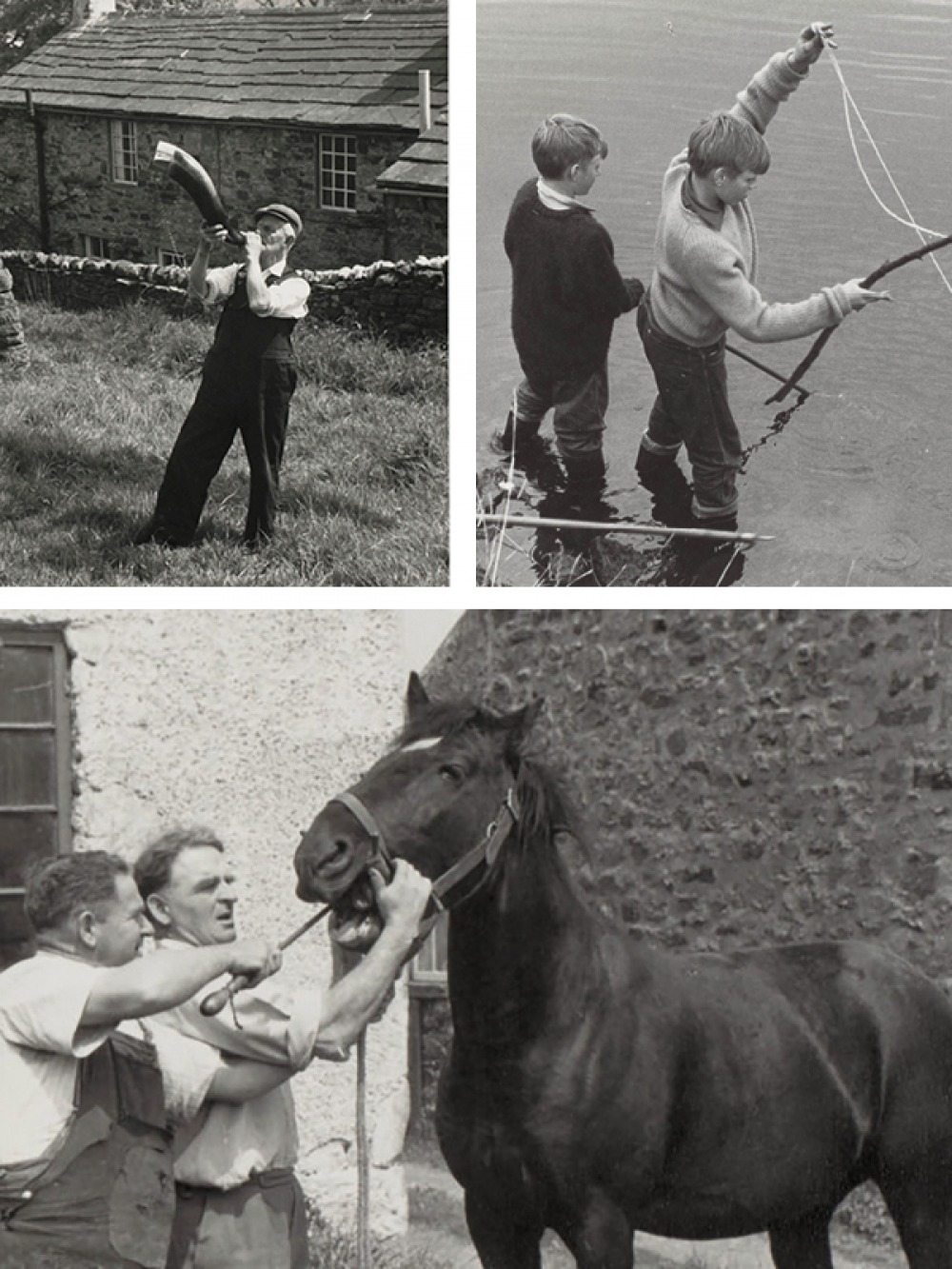

'These researchers conducted the Survey of English Dialects, asking people from roughly 300 places around England all their words for different things at a time when audio recordings were only just becoming portable,’ she explains.

‘They’d go to people’s homes and record from all over. The result is an incredible archive of audio recordings, photographs, and note books from field workers, and even drawings of items such as farm equipment that would be labelled with their regional words.'

‘We have an amazing opportunity to compare these older findings with modern dialect, especially as some of the people they spoke to were in their 80s and 90s at the time, meaning they were growing up around dialect from the 1850s!’ Rosie marvels.

‘You can listen to these recordings on our website and it’s absolutely incredible – it’s like travelling back in time.’

On The Great British Dialect Hunt’s website a sound map can be found with audio clips from the 1950s, digitised for the modern day. These include a description of making a cartwheel by Thomas Moscrop from Heddon-on-the-Wall in 1953, a tale from a Washington resident about a mate who got locked out of the house, and an incident with a horse and carriage in Haltwhistle.

‘We’re not just interested in old dialect, we also want to know how dialect has changed,’ says Rosie. ‘People move around a lot more, they pick up words from colleagues that grew up in different places, from their partner if they settle down away from home, and sometimes people carry words with them,’ Rosie explains. ‘We call these “inherited words”, words that can be passed down from grandparents that you may not have even met.’

Inherited words often come to mind when thinking of loved ones. Being from Grimsby Town myself, I think of ‘spoggy’ for chewing gum or a ‘pag’ for giving someone a lift on their bicycle. As a researcher, Rosie has encountered countless words she’s fallen in love with, some she grew up with and others learnt.

‘I pinch myself all the time to remind myself that this is my job. Sometimes words crop up from my own dialect inheritance, words like “fizzog” for face or “luggy” for knotty hair – “cakehole” is an old favourite from my grandad, meaning mouth,’ Rosie reflects.

‘I’ve learnt loads too, like “clodhopper”, which was used in Shropshire back in the 50s to mean a ploughman. Also funny phrases like “hark at he you’re driving the pigs home”, which means someone’s snoring loudly in South-West dialect,’ she laughs.

Contrasting oversimplified debates about the North-South divide, Rosie believes the variation in language between nearby communities is far more interesting to compare.

‘Language changes all the time, that’s one of the most fascinating things about it. We’re not trying to change that’

‘In the North East you get fine-grain variation from village to village or city to city; people make generalisations of the North vs the South, but in reality it’s far more interesting than that,’ she continues.

‘From the original archives, researchers were collecting different words for “skiving” or “bunking off”, skipping school essentially.

'In Bickerstaff in West Lancashire, they said “playing hooky”, but four miles North in Ormskirk they got “playing twag”, compared to way up North in Newcastle where they heard “playing the knick”.’

Dialect is an important way in which people anchor themselves to their family history. Culturally, it connects people to their homes and passes regional identity down to their children.

'That doesn’t mean we should mourn language when it changes, however. Instead, all dialects should be celebrated and all dialects should be preserved.

‘Language changes all the time, that’s one of the most fascinating things about it. We’re not trying to change that,’ Rosie explains.

‘Dialect really matters. It matters to people in terms of their identity – it sounds like home, it makes you think of home. It’s a way of connecting to place, you can move around the country, but those words still take you back,’ she continues.

‘You also pick up new words and it’s important to research this so we can properly understand the process of language change. Sometimes people worry that dialect will die, but dialect can’t die – it just changes. That’s not something we can stop, but it is something we can take a snapshot of and preserve for future generations.’

We’ve already clarified that there are countless dialects out there, meaning Rosie and her researching peers are going to need all the help they can get. Rosie shares some of the ways you can get involved.

‘If you go to our website you can fill out a dialect survey. You can also test your knowledge with a quiz, and you can listen to voices from the past on our interactive sound map,’ says Rosie.

‘You can record your own voice to submit to our findings and we’re hoping to use some of these recordings to make an immersive art experience – a soundscape of people’s experiences.

'Across the country we also have five partner museums, actings as hubs with engagement officers at each, sending out field workers to interview people. Some of those people being targeted are the descedants of the original interviewees from the 50s, so we’re going to have an amazing picture of then vs now,’ she concludes.

Get involved at dialectandheritage.org.uk

Midden

Dung heap, Stamfordham 1939

Gimmer

Young female sheep, Humshaugh 1939

Poddish

Porridge, Belford 1938

Teddies

Potato, Lowick 1939

Marra

Friend, Washington 1953

Hewer

Miner, Washington 1953

Fuzzcock

A donkey

Dowly

Feeling unwell

Brussen

Grumpy, agitated, rough around the edges

Cletch

A family of young (e.g chickens or children)

Pankin

An earthenware pot

Hirings

An annual fair for hiring farm labour